"[T]he values to which

people cling most stubbornly under inappropriate conditions are those values

that were previously the source of their greatest triumphs."

- Jared Diamond, Collapse:

How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed

In Collapse: How Societies Choose to

Fail or Succeed, Jared Diamond (UCLA professor of Geography) described

the collapse of civilizations as a gradual environmental process, fueled by

systematic behavioral weaknesses evident in inertia and short-term thinking,

culminating in a rapid unwinding too rapid to stop. As he describes it,

as environmental stress increased in prior failing societies, social and economic

disparities widened. Rather than looking to identify empirical causes and

create functional solutions to save themselves, these societies fractured

along political and class lines. As stress increased, the various factions

hardened their tactics, ultimately physically attacking internal political

enemies and igniting civil wars which destroyed the social and cultural mores

that upheld institutions.

I was reminded of Diamond's thesis a few weeks ago in Canada, of all places.

I was in Toronto's financial district when I was handed, with a direct and

sincere look, a manifesto on the evils of capitalism.

Now, when I lived in San Francisco and Austin (two cities I love), I often

received such manifestos - usually followed by some unsolicited recommendations

regarding marijuana cultivation or freeing Tibet. It was all fairly benign.

But the Toronto pamphleteer was not unhinged, malodorous, or intoxicated - he

was sincere, healthy, and appeared overtly rational. His apparent

reasonableness shocked me more than the manifesto itself: A reasonable man

pushing an overthrow of capitalism. That same night, student riots in

Montreal over tuition

increases led to the arrest of 122.

Democratic governments in the developed world have borrowed money to finance

their promises. Without displaying adequate performance. As a

result, voters are disappointed and angry, and now inclined to try extreme

alternatives.

While I'll discuss social collapse in light of Greece this week, I think we

should also take this opportunity to look at our own societies. The

unraveling has already begun. What can we do to prevent a similar meltdown?

I consider myself optimistic, so it pains me to return to the topic of

collapse. That said, I'm of the opinion that facing an ugly truth sooner

allows us to have a happier life later. Sadly politicians have the incentive

to avoid hard choices in the short term, and as a result the pain of collapse

will be that much greater.

New public policies that

account for human (and elected official) psychological weaknesses are

desperately needed. Fortunately, such an effort has begun. Read

on to learn more.

But first, some

housekeeping...

Istanbul, Toronto, London, and Las Vegas

|

In the past month we've been

speaking and training in Toronto, San Diego, Quebec, Las Vegas, and Istanbul

(what a lovely city!), and we'll be in London,

Las Vegas and Quebec (again) in the next 30

days. The London News Analytics

Roundtable in

Canary Wharf on June 18th is

a must-attend if you use sentiment data. We look forward to catching up

with our friends in those cities.

We still haven't launched our weekly investment newsletter,

but we're on the verge (just two more weeks)! Click here to receive our weekly investment strategy newsletter (if you already requested the Newsletter,

then this step is unnecessary). We've

been intensively expanding our data architecture in order to capture even

more interesting data and predictions to share with you.

We will also be adding separate financial advice and global

social commentary in separate monthly newsletters. More about those as

they prepare to launch.

I'll be relocating to the New York City area this

summer. It has been wonderful in California, and I hope to return to

the San Francisco area soon - but for now family and clients bring us East.

|

Fearmometer

June 12,

2012

Recent Press

For Financial Advisors:

Advisor One. April 26, 2012.

|

Peek-a-boo, Object Permanence,

and the Surprising Event That Couldn’t

|

Last year I commented to an

acquaintance of mine in Europe, "I wonder how long until the Euro falls

apart?" He dismissively remarked, "The Euro won't

dissolve. It can't." When I asked why it can't, he explained,

"Well, what would happen then? It's impossible." This

line of reasoning is a bit like telling Columbus in 1492, "No one knows

what is over the horizon, therefore you cannot sail that way." This

flawed logic reflects a psychological stage of child development called object

permanence.

Object permanence describes an infant's growing recognition

from birth to age 2 that objects

he or she cannot see, hear, or touch are still existing. The concept of

object permanence explains why peek-a-boo is such a hilarious game for

infants. When you disappear behind a couch, they truly feel, "Oh,

how disappointing!" And then you suddenly jump up and reappear,

prompting a happy revelation: "He's back, what a thrill!"

And giggling ensues.

Adults have a similar problem

with inconceivable outcomes - if a potential outcome is too complex or

unprecedented, we ignore it (and don't prepare for it) because it is

impossible. As an adult might say, "It is impossible for countries

to leave the Euro because the consequences are unfathomable." This

statement is a bit like a child playing peek-a-boo - if I can't conceive it, then

it doesn't exist in the realm of possibility.

The last four years we've been

playing peek-a-boo with the specter of first Greek default and then Greek exit

(Grexit) from the Euro. Every six months the specter pops up again, and

markets react with the same incomprehending fear until a stop-gap is agreed

upon.

Catastrophizing or Total

Disaster?

|

The fear of Grexit and

financial Armageddon caused credit markets to freeze - as European credit

markets did the past few weeks. Each time this has

occurred previously in the past 4 years, governments step in as counterparties,

the specter of crisis dives behind the couch, and the market's short-term fear

is dissipated.

Every time credit markets

freeze, a catastrophic concern emerges - that this time the specter will

"get us" and financial collapse truly will ensue. The concern

is a logical one that arises from experience with herd behavior: If you

are a lender, and your peers are also beginning to restrict credit, then you

yourself are incentivized to stop lending. No one wants to be caught

holding the bag. So each lender tries to stop lending first. This

cycle is repeated every six months and is only stopped by a convincing

short-term response from political leadership.

Our news and social media

monitoring software shows this cycle in conversations about Greece. In

Greece, the focus of anxiety is shifting over time. In the image below,

all lines represent levels of conversation about Greece specifically. In

the image are significant spikes in chatter about Greek Unemployment beginning

in Spring 2009 (blue line), in late 2009 Fear rises in conversations about

Greece (pink line), and in April 2011 a Greek Debt Default becomes a real

possibility according to the media (red line). Was it the rise in

unemployment that ultimately sparked high stress in Greece? As fear

remained high around Greece, more extreme events were facilitated.

Ultimately, debt default became more concerning, and then occurred.

SOURCE: Aleksander Fafula, PhD

As we described in our

webinar last Fall, democratic citizens will not

vote for politicians who keep the pain coming. Witness Sarkozy's loss,

the rise of Tsipras in Greece, and the surprising success of the brutal Greek

far right party - the Golden

Dawn. So what will a stressed public do? They will vote for severe

short-term pain ("rip off the band-aid" therapy) in order to escape

the cycle of continued slow suffering. This is capitulation, a precursor

of economic collapse.

Overestimating

Low Probability Negative Events

|

Cognitive

psychologists have identified numerous emotional biases that distort our

thinking when we are feeling stress. These biases have self-explanatory

names such "black-and-white thinking",

"over-generalization'", and "catastrophizing." Catastrophizing

is the bias I'd like to use to illustrate what is happening to the thinking of

the European public. Catastrophizing refers to overestimating the odds of

severely negative events happening.

Catastrophic

thinking has its roots in our genes and neurochemistry. Think about

it: it was better that our ancestors over-estimated the odds of a

disaster than underestimated. They would have been culled from the gene

pool if they were under-prepared for potential danger, if it actually

struck. As a result, we are descended from "Nervous Nellies."

We are hardwired to think the worst in dangerous situations.

The most

apparent example of catastrophization occurs in the way we estimate

probabilities of unlikely, but potentially severe, events. The image

below depicts our overestimation of small probability negative events.

"Affect-rich" refers to the odds we place on events that have vivid

and emotional signs, like riots and burning buildings in Greece.

"Affect-poor" refers to the odds we place on objective, boring

events, like the chance the next Euro notes will have a picture of the

Copenhagen-Malmo (Øresund) Bridge. As the curved line deviates above the

straight diagonal line, it represents the increase in estimated probability

above the actual level for Affect-Rich (high emotion) events. Affect-Poor

events are also overestimated, but less so.

Fortunately,

we do not have to be passive victims of our own catastrophizing.

Cognitive psychologists have found that we can consciously supplant anxious

thoughts with unbiased and objective thoughts, thus reducing the core emotion -

anxiety - and interrupting the positive feedback loop and mental

"spinning" that anxiety causes. Consciously thinking unbiased

thoughts acts to calm anxiety, and thus we can intentionally modify our

thoughts via cognitive therapy techniques, reducing biases such as

catastrophizing.

In the

case of Greece and the Euro-zone, it's important to keep this in mind as the

crisis intensifies. We are all emotionally primed to feel anxious by the

media. As investors, however, it is key to remain objective (and

contrary) about the herds' emotion. The best way to remain objective is

to consider the cognitive processes that have already and that will unfold

among European leaders, voters, and investors. The four Researcher's

Corner sections below articulate findings that shed light on how humans

repeatedly get into bad financial situations through short-term thinking, why

we "kick the can down the road" to avoid short-term pain while

risking longer-term disaster, and how a final capitulation occurs.

Researcher’s

Corner: Self-Control

|

This May Harvard behavioral

economist David Laibson gave a fascinating talk at UCLA about some of his

latest behavioral research. Dr. Laibson is well-known academically for

adapting a hyperbolic discounting model (the beta/delta model) to describe how

people make saving, spending, and investing choices. He's also done

terrific work on cognitive decline and financial decision making, which we cite

in our MEMRI script for

financial advisors.

In his recent UCLA talk, Dr.

Laibson described research he performed with John Beshears (of Stanford) and

colleagues. They tested a model of savings in which subjects were given a

choice of a "liquid" savings account (they can withdraw money at any

time) versus a savings account with an early-withdrawal penalty. After

one year, the subjects who kept their money in either savings account would

receive the original savings plus a 22% return. The researchers tested

several combinations of punishments for the early-withdrawal condition.

Some could choose to receive their experimental earnings either in the freely

liquid account or in the one with a 10% early-withdrawal penalty. Another

group could choose between the liquid account and an account with a 20%

early-withdrawal penalty. A third group chose between the liquid account

and an account with no ability to withdraw funds until the year was up (a

lock-up account). Remember, the subjects received a 22% annual return on

their savings in whichever account they chose.

Rational expectations theory

assumes that people have perfect self-control, and as a result they should

choose the fully liquid account option (in case of an emergency or a higher

available return, they could then withdraw the saved money for that

purpose). Contrary to rational theory, many people chose to use the

penalty-accounts with the percentage choosing the penalty accounts increasing as the potential penalty

increased. More than 20% of subjects chose the 10% penalty account in the

first group. In the second group more than 30% of subjects the 20%

penalty account, and in the no-withdrawal condition more than 50% of subjects

chose this account for their savings versus the liquid account. Many people voluntarily chose future

punishment in case they withdrew their money early. Technically speaking,

people will chose the threat of punishment against their future selves in order

to enforce self-control on them.

So we know that we are weak at exerting

self-control over our savings. Are our government leaders equally as

weak? There is no checks-and-balances system set up to prevent

politicians from over-spending. Yet in a democracy, elected officials

have an extra incentive to boost spending for their constituencies in advance

of voting. The result of such overpromising is that social security and

healthcare promises are easy to make before elections, but eventually those

promises come due. The developed world is now faced with an obvious

negative predicament - our future promised liabilities far exceed our ability

to pay them. Most governments can print money to fund liabilities (a

stealth tax via inflation) and use stimulus measures, but there is moral hazard

with such a solution - the fear that there is no end to such printing by

elected politicians once it is made morally acceptable. Yet fiscal

austerity creates short-term pain, and if it does not lead to growth within a

2-year election cycle, then it is often abandoned by politicians promising easy

fiscal solutions (stimulus). So what can we do to break this cycle?

To understand solutions, we must first understand how we got into this

position.

Researcher’s

Corner: Moving from Hope to

Capitulation

|

Psychologist Daniel

Kahneman shared the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economics for his development of

Prospect Theory with Amos Tversky. Prospect Theory is a model of

decision-making under risk, based on experimental evidence (in contrast to most

economic theories), that describes how people decide when faced with

potentially negative outcomes (risk).

It turns out that

people behave very differently depending on their "reference points"

(essentially, their expectations). For example, when people are in a bad

situation, and they have hope of recovering via perseverance, they generally

INCREASE their risk-taking. This increase in risk-taking is also

called "doubling-down" and is driven by what Hersh Shefrin and Meir

Statman called the disposition effect (a.k.a. "breakeven-itis" - the

desire to get back to a neutral position). This is the psychological

process that drives that bane of traders, "holding onto losers too

long." Holding onto losing positions too long (in the form of

"throwing good money after bad" and the "sunk cost" bias) is

also a scourge of taxpayers and is seen in expensive never-ending over-budget

military projects like the "stealth bomber" and infrastructure

projects like "the Big Dig" in Boston.

The Euro-zone has so

far thrown tens of billions of good money to Greece (and now $125 billion to

Spanish banks) with the hope that after receiving this money, Greece would

reform. Greece not only did little to reform its tax code or pensions

system, but also many Greek voters spurned the bail-out, labelling it German

imperialism. Europeans might justifiably feel a bit angry by the

intransigence of the Greek government. And it is this anger, as it gives

way to hopelessness, that will reset the European reference point

(expectations) from hope to despair - from potential recovery in Greece, to

Greece as a lost cause.

But while hope has

given way to despair regarding Greece, there is still - on balance - hope that

the remaining members of the Euro-zone can find a solution for themselves.

Researcher’s

Corner: Buy on the Rumor, Sell on the News

|

Neuroscientist Wolfram Schultz

demonstrated that our brain's learning mechanism is fueled by one of the

brain's dopamine circuits (the meso-limbic, which runs through the reward

system). Interestingly, this system is most responsive to expectations

(the reference point). When expectations are increased by rumors or

potential positive events, a surge of dopamine is released. When the

expected event happens, if it is in line with expectations, then the dopamine

level does not change.

When rumors of a Spanish bank

bail-out hit the news, world financial markets rallied and finished last week

as their best week of 2012. The reward systems of traders were excited by

the anticipation of some relief. After the Spanish bank bailout was

announced, European markets gapped up on the good news but ultimately sold off,

down more than 1% for the S&P 500 by end-of-day. So what happened?

When positive expectations are

met (or worse, disappointed), then the dopamine system deactivates, leading to

decreased dopamine activity and decreased risk taking. In the case of

traders, such deactivation from calmed expectations leads to selling.

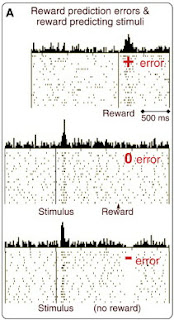

Below are Schultz' images of

how the brain's dopamine neurons in the reward system respond to rewards

("Reward") and how they respond when expectation of reward are set

("Stimulus"). Notice that the frequency of dopamine neuron

firing increases in the second image when the stimulus is received (and

expectations are set), but decreases very slightly when an expected reward is

received. Dopamine firing pauses entirely in the third image when the

expected reward is not received ("no reward").

SOURCE: Schultz, W.

2011. “Potential Vulnerabilities

of Neuronal Reward, Risk, and Decision Mechanisms to Addictive Drugs.”

Schultz' work is relevant to

the Euro crisis because it can trace much of the price volatility to the fear

of disaster, then expectations of short-term salvation (saving the Spanish

banks), then disappointment when expectations are met (or disappointed), and

finally the next crisis looming into view. When Euro-zone leaders meet,

expectation (and hope) is high that they will present a coherent plan.

When they do not present a workable plan, markets plummet. Sometimes

European leaders surprise with temporary relief measures, and the markets rally

for a few months until it again becomes clear that Euro-zone economies are

worsening, thus necessitating further bail-outs.

This cycle of

expectation-setting, disappointment, and relief is emotionally exhausting for

market participants. More importantly, it becomes exhausting for the

European public and the leaders themselves. Such exhaustion leads people

to try to escape from the noxious situation. If positive means of

resolution are not found after 2-3 years, then drastic measures are viewed as

more desirable - anything to "stop the pain", including more severe

short-term pain as long as some ultimate relief can be seen on the horizon.

As long as there are multiple

potential outcomes (uncertainty), investors will shun European equities and

bonds and eventually the Euro. At this point, a workable plan will

involve political and budgetary check-and-balances, if not a direct political

union, to balance the monetary union. Once that uncertainty is

resolved (a "probability collapse" in psychological jargon), a real

relief rally will ensue.

Democracy

and Financial Self-Control

|

The founders of the United

States appeared to understand the human psychology of power (and the ease of

corruption). As a result they designed a governmental system of checks

and balances between the executive, legislative, and judicial branches to

prevent excess power in one branch.

Yet democracy can be

undermined by excessive short-term thinking with finances and budgets.

There is no legal check on the power of legislators to over-promise and

overspend, and voters have little ability to understand (nor react

appropriately to) fiscal profligacy among leaders.

Fortunately a group of UCLA

behavioral economics researchers founded a behavioral policy journal to

stimulate ideas and research in improving public policy through an

understanding of behavioral incentives. The journal's founders also

provided the Obama campaign with strategic tips on boosting fund-raising.

The George Clooney celebrity dinner? Yes, behavioral

economics-inspired. The lottery for a "regular-guy" seat to

that dinner? Also behavioral economics in action. One enjoyable

aspect (perhaps the only pleasant part?) of this year's U.S. presidential

contest will be watching behavioral strategy employed. We've expanded our

text-analytic software to include political figures, so we'll keep track of the

major races this year out of personal curiosity and will keep you posted on our

findings.

Clearly there is a lot of fear in Europe. Below is an

image of the amount of Fear expressed in all news reports about Italy versus

the United States through January 2012. For several years Italy managed

to avoid the contagion of the Euro-zone instability. But now fear is

squarely on Italy's doorstep.

Because of such fear in the

Euro-zone, investors have fled in droves. The Economist Magazine recently

noted that European equities are trading at an average P/E ratio of 11, while

U.S. equities have a P/E of 18. As a result, European stocks are

"cheap", and once the uncertainty is resolved, a massive rally may

ensue. Southern European bank stocks are a call option on a Euro-zone

reconciliation, but there is a risk of nationalization of dysfunctional banks.

Financial firms that were indiscriminately sold alongside European

banks, such as insurers and brokerages, are better investments.

In the short-term, the next

anticipated event is the Greek election of June 17th. The outcome is

uncertain, but a favorable short-term result (favorable for Greece to stay in

the Euro) is likely. That said, Germany still must decide whether or not

to deliver additional bailout payments, and given Greece's lack of tangible

progress in reforming their tax collection system and pensions, additional

bailout funds are uncertain.

Ultimately, the European

volatility will continue, to be followed by an acrimonious American

election. Yet as Warren Buffett has said, "The future is never

clear, and you pay a very high price in the stock market for a cheery

consensus. Uncertainty is the friend of the buyer of long-term values."

That said, any relief rally

will likely last for months of duration (not years) and then stall. The

demographic headwinds facing Europe are significant long-run drags on the

equity markets and economic growth. The uncertainty developed world

markets face is more fundamental than at any time since the Second World War.

Keep your chin up - this summer

is a time to be thoughtful and opportunity-seeking during the short-term waves

of anxiety as they sweep over markets.

We love to chat

with our readers about their experience with psychology in the markets - we

look forward to hearing from you! We

especially love interesting stories or your or others experiences.

Happy Investing!

Richard L.

Peterson, M.D. and The MarketPsych Team

Books

Both books named "Top Financial Books of the Year" by Kiplingers.